For LJB

Hannah Arendt differentiates between thinking and violence: “a gulf separates the essentially peaceful activities of thinking or laboring and deeds of violence.”1 She is certainly positive about thinking itself, outlining the man-creating-himself philosophy of “I think, therefore I am.” Arendt decries a trend in Jean Paul Sartre and Franz Fanon’s thinking on violence. She is particularly against the idea in both philosophers that violence is something creative and/or biological. Sartre and Fanon are evolutionary thinkers who believe in the animal instinct of man. The race of man against other men is contextualized, here, in the theory of survival, and in the animal kingdom. Later in the 19th century, the Freudian obsession with sexuality, and the subconscious, also relied on the evolutionary thinking that an animal lay sleeping inside us. In other words, for the decolonizing Fanon, the awakening of the creative madness in the psychology of the colonized subject was a matter of survival, an awakening of the sleeping violent animal. Violence, according to Fanon, was absolutely necessary to decolonization.

Following the conviction that decolonial violence is biological, musicians like Bob Marley wrote songs like “Small Axe:”

If you are a big tree,

We are a small axe,

Sharpened to cut you down

The song follows the kind of man-creating-himself philosophy that Hegel described, as man becomes himself through thought. The decolonial thinking that produced “Small Axe” relied on a visceral creativity that inspired and provoked violence. These kinds of songs became the motto of decolonization, among activists for whom violence was not only metaphorical but biological. The creativity of decolonial philosophy only reinforced this conviction. And yet we can safely say that when violence became real, they swallowed white ants—fear gripped them, fighting wore them, war scarred them. The political formations that pierced Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean in the 1960s, left scars visible today.

In my research on the period after Independence in Uganda, musicians particularly became enemies of the state, if they continued with the criticality that decolonization philosophy encouraged in the arts prior to Independence. Many decolonization philosophy encouraged in the arts prior to Independence. Many dramatists and performers were murdered for critical commentary on Idi Amin Dada, the Ugandan dictator, for example. In Nigeria in 1977, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti’s mother was thrown off a balcony after the musician released the highly critical record, “Zombie”—about the Nigerian military. Decolonial thinking itself, with its fierce calls for violent action, became a double-edged sword in the hands of musicians as they walked on thin ice with militant postcolonial governments. A natural solipsism of big trees and small axes—Arendt says that these man-creating himself philosophies “have a common rebellion against the human condition itself.”

——

The anti-war poet Siegfried Sassoon wrote, “Soldiers are dreamers, when the guns begin.” The line is from a 1918 poem called “Dreamers” pointing us to a time before the guns opened fire in World War I. Towards the end of the poem, it becomes obvious that Sassoon differentiates between the dreams of a soldier and the favorable descriptions of their waking life. It is quite similar to the theory of dreams by Carl Jung, which considers that dreams should be interpreted alongside the waking life of the dreamer. This interpretation is alongside the everyday images of “firelit homes, clean beds, and wives” as well as “Bank holidays, and picture shows, and spats.” In the theory of dreams, these images devised by the poet, are meant as a cautionary reminder to the soldier, and the reader, of the “perfect” life before the war broke. Sassoon places in the poem a slide of images, which appears as propaganda showing the horrific nature of war in “death’s grey land.” This slide includes: “foul dug-outs, gnawed by rats, (soldiers) in the ruined trenches, lashed with rain.”

In the 1968 poem “Momentos, I” by W. D. Snodgrass, an image occurs that recalls Carl Jung’s notion of primordial images in his theory of the “Collective Unconscious.” Here, the narrator describes a discovery of “That picture,” which becomes the center of the poem’s drama.

“I stopped there cold

Like a man raking piles of dead leaves in his yard

Who has turned up a severed hand.”

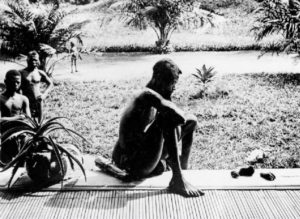

The image of the severed hand is a doppleganger of the Alice Harris 1904 photograph of the man sitting on a veranda in Congo, in front of a severed hand and foot. It is a fantastical image that appeals, with its psychology, to what Jung describes as “patterns of instinctual behavior.” The psychologist refers to motifs that are not easily identifiable in the patient’s own memory. As if the image were coming from another time and dimension. As if the image were otherworldly. Certainly, Snodgrass uses the image metaphorically, to show the extent of horror, of distance, and of time that has stretched itself between two lovers. The main character is on a battlefield of “the Japanese dead in their shacks / Among dishes, dolls, and lost shoes.” This is where the narrator finds the photograph of their exwife, years apart from the moment depicted inside the image, “before (they) got married.” The metaphoric severed hand carries all the weight and burden of experience, of fracture, of deracination that the narrator feels.

Carl Jung describes a method called “active imagination” as a radical attempt to get the dreamer closer to understanding the motifs and patterns of instinctual behavior. “By this I mean a sequence of fantasies produced by deliberate concentration,” Jung writes. I find two aspects of this method useful in unpacking the body of propaganda images that came out of the Congo in the late 19th century. The first is in how the horrors of slavery were pictured. The photographs of slavery in Congo were meant to expose the ills of the Arab-Swahili slave trade. Second, the sights of slavery’s horrific details were not of the everyday. It seems that photographers, aware of the acute uniqueness of these incidents, produced fantasies meant to expose the sickness of slavery. It is in the deliberate concentration on the fantasies of slavery that photographer Alice Harris, and her husband, practiced an active imagination, which led to bringing forth of such fantastical images as the severed hand.

——

“Why don’t you just do me like Kunta Kinte and chop off my foot?” asks a character played by Will Smith in the sitcom, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. The “chopping of the foot” evokes comically the fear of punishment for an offense. But the punishment refers to a real practice from the 18th Century in America that involved cutting the foot of the slave that attempted to run away, first as punishment for the attempted escape, and second, to make it difficult for the slave to attempt escape again. Kunta Kinte is the main character from the TV series to attempt escape again. Kunta Kinte is the main character from the TV series Roots (1977) written by Alex Haley.

Haley was at this point a master of oral history, having shown his talent for orature in his first book The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965). Haley had worked with the subject of this book in depth through interviews in which Malcolm gave oral accounts of his life. In this sense, memory is a hugely important part of Haley’s writing. The detail that stands out in the TV series, and can be replayed on YouTube, is when Kunta Kinte gets his foot cut off as punishment for attempted escape. The question is how does one understand this image of the cutting of the foot?

Besides blood splattering all over, there is a deafening scream of the actor LeVar Burton. Because this filmic re-enactment is an image of slavery, it belongs to a body of images that began circulating in the 19th century. I am tempted to refer to the dramaturgy of this particular scene of the cutting of Kunta Kinte’s foot as a form of “active imagination.” It belongs to the realm of heightened fantasy, and the resulting severed foot to Jung’s primordial image. I believe that Alex Haley constructed the image from the oral histories that he overheard growing up in the South. As a result, a sense of trauma is evoked in the narration, but the encounter of those who saw it, with the severed foot remains in the far distance of time and family lineage. Yet Jung describes how these horrific experiences can re-emerge in the mind: “Endless repetition has engraved these experiences into our psychic constitution, not in the form of images filled with content, but at first only as forms without content, representing merely the possibility of a certain type of perception and action.” What the oral storytellers may have been struggling with in the cutting of the foot is precisely this notion of a form without content, like a ghost which one can describe, but cannot attach a clear meaning.

When considering trauma itself, it has less to do with the action of the cutting of the foot, and has more to do with the perception of those who lived to tell the the foot, and has more to do with the perception of those who lived to tell the story. The connection between how people encounter a violent incident, its horrific details, and how this violence lives on in memory, is the narrative theme of Toni Morrison’s novel Sula. It is here, in this novel, that fantasy, and, in its pathological reach, neurosis occurs, as the narrative plot in which characters tell and retell, remember and misremember violent history. The concern of Morrison is the when and how of the ambiguous and precarious encounters with violent experiences; how these characters carry around the burden and the weight of things long lost.

Eva, grandmother of Sula, does not narrate for everyone how she lost her leg. In fact, the lost leg becomes a mythology of its own, as we never have a close-range encounter with Eva losing her leg. After Eva returns to the Bottom on crutches, we wonder for the rest of the novel, how hard, how difficult, how sharp the pain must have been to lose the leg. This one violent experience colors the novel in unpredictable ways. Even as Eva struggles down the stairs, we feel every step she takes, misremembering what happened to her and how terrible it was.

——

The photograph of the man sitting on the veranda is one of those in which we get to the sitter after the violence has passed like lightning, and we cannot recover it fully. What is available is the pensiveness that draws us in, like a slow thunder, combined with the dramatic Rembrandt-like silhouette. We wait for the two men in the wings, by the side of the veranda, to come in; we wait for them to interrupt the scene, but they never do. It is possible that the man was sitting there a long time. He looks as if he has suffered a trauma, or is about to.

This image comes to me like the smoky voice of a ghost-father in Li Young Lee’s poem, “Have You Prayed.” The narrator hears his father’s voice sitting alone in a hotel room years after his father’s death. In my encounter with this photograph, there is no ghostly voice instructing the sitter. But this does not stop introspection. This does not stop the incredible arching of the body. This does not stop the sense of defeat. Trauma is clear. So clear that the scene reconstructs the psychological parable: great insight comes from a severe loss of consciousness.

In short, death.

Before him are two human organs: a hand and a foot. They look relatively smaller compared to his own. Could it be that the man is looking at his hand and foot? The background tells us otherwise. This is a colonial styled home. A potted aloe-vera plant and the extravagant palm trees in the garden with the trimmed grass reveal something else: this couldn’t be the sitter’s veranda. The question lingers: why is the man sitting on a settler’s veranda staring at a severed hand and foot?

——

Recently circulating on Facebook after news of Harriet Tubman on a dollar bill broke is a meme with a 19th century photograph of a slave girl. The meme reads: “When Your Slave Master Thinks You Gon’ Be Working For Him Forever But You Leaving With Harriet Tonight.” Tubman made it easier for slaves to run away, with the assurance of limbs intact.

——

We know that this photograph comes from Congo, dated 1904. And there, slaves also lost their limbs. In the rubber boom of the late 19th century, King Leopold of Belgium accumulated mass wealth from the rubber trade. There’s another image accompanying this one in which three slaves in a Congo forest are harvesting tree sap, which pours like milk into a gourd. The caption describes the working conditions of Congo slaves: they were forced to pour the liquid sap on their bodies and then forcibly remove it, at gunpoint.

The horror of the Congo Free State, the irony of its name.

——

In 2015 I visited artist Issa Samb’s studio in Dakar, where he showed us a sculpture in his yard, by the artist Ndary Lo. The sculpture was a crucifix, and likely related to another work in the yard, a body covered in white sheets, with a crucifix on top. I was very taken by Issa’s dramaturgy which seemed so natural as to erupt from thin air, his relational emphasis on signs and metaphors that connect death to life, and the vast amount of wandering and searching that we did that day in his yard reminded me of the post-nationalist art group he co-founded in the 1970s Laboratoire Agit’Art.

I first heard of the Laboratoire on my first trip to Dakar in 2014. I had been thinking about 1970s Ugandan musicians that used metaphor to write politically charged lyrics, which often made them enemy of the state. The Laboratoire, it seemed to me, resonated deeply with a theme I was exploring: artistic transformation after political violence. The group had produced an aesthetics that signalled artistic transformation in the 1970s, at a time when art and the production of art in Senegal had been nationalized. In outdoor theatre performances and installations, Laboratoire worked with everyday objects: clothes, shoes, dolls, doorframes. Clementine Deliss who curated the work of the group in the 1990s, remarked that an audience in Sweden could not understand the participatory nature of the work: one of which was a door frame that one had to walk through.

Ndary Lo’s sculpture comes to me like the smoky voice of a ghost-father in the Li Young Lee poem, “Have You Prayed.” A more recent work by Lo—hands stretched out like tree branches—appears like the primordial images Jung describes. Lo’s work is fantastical within its hands that reach out and above, more so when contrasted with the image of the sitter on the veranda, before a hand and a foot. Ndary Lo’s tree-hands evoke the thought: what freedom, in a way that the severed hand lying before the sitter never could.

Notes

1. Arendt, Hannah. On Violence. New York Review of Books. May. 1969