I begin with facts available in the public record.

Sometime in mid-May 1899, the Benin warrior known as General Ologbosere was captured for leading a guerrilla war of resistance against British forces. Two years prior, Ologbosere masterminded an attack on a British expedition outside Benin, killing at least ten Europeans and two hundred African carriers. Retribution was prompt, and an armed expedition was organized. Five weeks later, Benin was captured. The king was deposed and exiled, his Empire annexed into the colonial administration. Ologbosere and four other chiefs maintained a resistance outside the city, hiding in, and launching offensives from villages that supported the resistance. The British forces, in response, burned those villages, destroyed crops, detained young people, and incarcerated rulers. Eventually war-weary villagers betrayed Ologbosere and his cohorts. Less than two months after his arrest he was hung alongside two others. A day before his execution, contrary to the testimony of the chiefs who decided that his life be forfeited according to native law, he contended that he was scapegoated. “The day I was selected to go to Benin City to meet the white men all the chiefs were present in the meeting, and now they want to put the whole thing on my shoulders.”

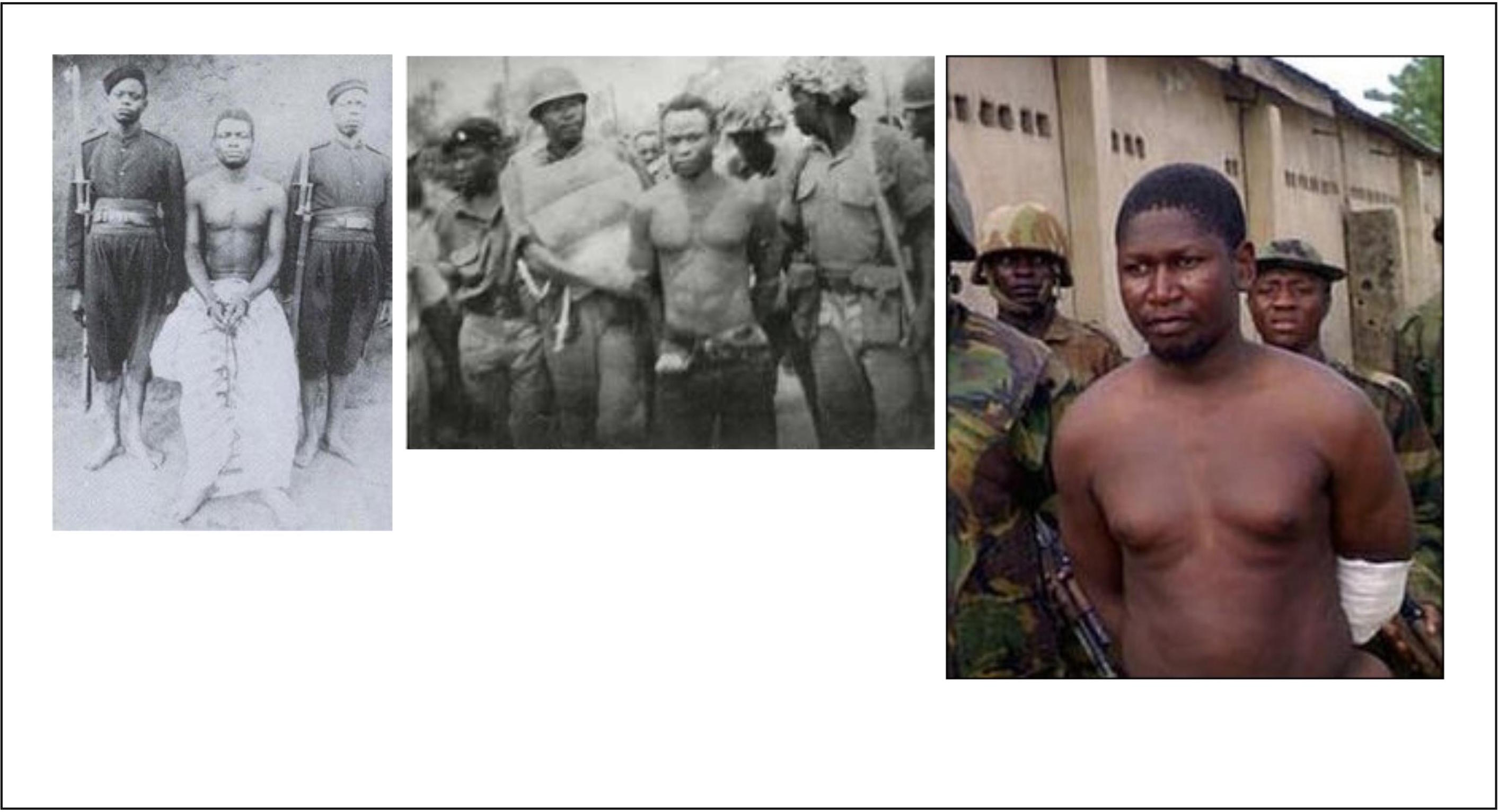

While Ologbosere awaits execution, a photograph is taken. He has been stripped to the waist and made to sit. He is handcuffed, flanked on either side by men of the colonial regiment.

A similar photograph, of Isaac Jasper Adaka Boro, was taken almost seven decades later. He is handcuffed, stripped to the waist, surrounded by men of the Nigerian army.

In March 1966, Nigerian federal forces arrested Isaac Adaka Boro. For days he’d led men of the Niger Delta Volunteer Service in a secessionist attempt to form the Niger Delta Peoples’ Republic. Fourteen days earlier, he supervised a brisk swearing-in ceremony where he gave marching orders to his men, known as servicemen. At exactly 6.30pm they marched off, chanting victory songs. Better armed government troops arrived the following day. After a week, it became armed government troops arrived the following day. After a week, it became foolhardy for Boro and his men to continue. Federal soldiers arrested relatives of servicemen, assaulted women, and looted houses. The revolution was called off. The secessionist fighters surrendered themselves in batches. Then Boro, their General Commanding Officer, turned himself in.

A third photograph, over forty years after Adaka Boro’s, shows Mohammed Yusuf. He is half-naked, surrounded by men of the Nigerian army, and handcuffed.

On July 30, 2009, when the Nigerian military captured Yusuf, leader of Boko Haram, he was said to have been hiding in his father-in-law’s goat pen. Four days earlier, the Nigerian military and police raided a mosque and several homes where Boko Haram members had regrouped, in response to the bombing of a police station. Dozens were killed. Mohammed Yusuf, in response, vowed to fight to die, to retailiate the killing of his followers. Coordinated attacks were launched that night across Maiduguri, in a small town in Kano, and in the capital city of Yobe. The military airlifted armored tanks and troop reinforcements to Maiduguri. Two days later he was captured, taken to a military barracks in Maiduguri for interrogation, then handed over to the police. There was a woman who lived near the compound of the police headquarters. She went with others into the station. They saw him sitting on the ground. This was about 6.30pm. He told the onlookers to pray for him. The mobile policemen wanted to kill him, but the commissioner of police wanted him to be left alive. Things escalated. Three mobile policemen shot him: on the chest and stomach, on the back of his head. The woman ran away. When she came back he was dead. A lot of people took pictures of his body.

*

I notice the security personnel in the three photographs. Men of the colonial regiment at attention beside Ologbosere, lacking in their stiffness his calmness; one of the two army officers whose faces are visible behind Yusuf looks irked and one of the two army officers whose faces are visible behind Yusuf looks irked and menacing. In Boro’s case, what is particularly striking is the grasp of the soldier on the left. Of everyone photographed close to Boro, this soldier is the only one who looks at him.

These gestures are necessary clues. How were these prisoners seen in those moments of submission? What did they become in the hands of their captors?

As widely circulated news images, transmitted mainly through the Internet, I speculate about their makers. Perhaps, for Ologbosere, a photographer attached to the Consul-General of the Niger Coast Protectorate. Or, for Adaka Boro and Yusuf, press photographers embedded with the Nigerian Army. Those details are secondary to the historical significance of the images. Once-feared, once-wanted men were displayed, subdued, emblems of the denouement of their stories.

Ologboshere’s photograph, in which he sits, is inarguably orchestrated—in 1899, you had to stay still to get a clear picture. Yet in that of Boro and Yusuf there is equally the possibility of orchestration. I suppose that, like Ologbosere, they were aware of a camera positioned to picture them. Whether they look toward or away their glances are steadied and their pose readied.

In all the time they battled the government they accepted the risk of capture. I know this as a possibility. Their faces are tranquil, even foreknowing. As if the matter is settled.

Once I triangulate their lives as men who were disillusioned with the status quo, who took to extreme measures to fight for their convictions, the photographs instantly elicit propositions hard to ignore.

*

A body stripped to the waist. Is that the ideal subordinated body?

Making spectacle of men adjudged treasonous, whether dead or alive, has historical precedence. Of particular relevance are those whose upper bodies are displayed bare. Consider two prominent instances of revolutionary figures from Bolivia and Haiti: In October 1967, a dead Ernesto “Che” Guevara is laid on his back, stripped to the waist. In November 1919, a dead Charlemagne Péralte is tied to a door, wearing only a loincloth. Surely a condemned body is one unfit of a dignified covering.

Dignity is cloth. This is the sort of metaphor that, in the images before me, has a propensity to turn literal.

If dignity is cloth, it can be separated from its bodily bearer. Such separation goes back to medieval times. Canonists and jurists of the time record that Roman Emperors were given double funerals. A wax image of the dead sovereign, representing his dignity, was treated as a real person. The image received honors and medical attention, and was burned in a solemn funeral rite. In later centuries the Kings of France were given similar double funerals.

The punishment for Ologboshere, Boro, and Yusuf was not only condemnation to death, but also the loss of dignity. Just as the Emperors or Kings were given double funerals, these men lost their dignities before bodily death.

In conceiving dignity, especially as cloth, I imagine the moment of public nakedness. When, perhaps, the men recognize they have reached the absolute limit of their conviction, certain death. That moment Mohammed Yusuf turns to the onlookers and cries, “pray for me!” This man who traded witticisms with his interrogators earlier, in a video recorded before he was killed, has realized his body is at their mercy. First it is healthy and uninjured, then bloodied and bulletridden.

*

There are the men’s bodies, and there are the men’s images. Their images have survived, central to how they are visible to anyone who returns to their stories as formative narratives of modern Nigeria. Might the unrehearsed similarities of the images point to a reverberation of events in Nigerian history? Arguably.

This reverberation makes me pair, for instance, Mohammed Yusuf’s arrest with Sambo Dasuki’s, the former National Security Adviser accused of laundering $2.1 billion voted for the purchase of arms to fight Boko Haram.

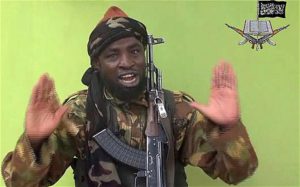

This reverberation is implied in the proliferated photograph of Abubakar Shekau, Mohammed Yusuf’s successor. In that photograph, his arms are held as if in mock surrender, wild and free. I see this and recall Yusuf’s cuffed and immobile hands.

To anyone who would need affirmation of the state’s control: here are condemned men, tendered in evidence. Yet they are also substitutes, held in place of calm, order, and control. As substitutes, they take the fall for all those who aren’t disillusioned enough to consider extreme violence an option. Recall Ologbosere’s recorded claim that he was a scapegoat, betrayed by Benin chiefs eager to ally themselves with the insurmountable British.

I return to the tranquil faces of the men. Where else to look to understand the meaning of their lives, the gravity of their convictions, and their inevitable condemnations? Each man, in his own way, seemed to welcome death. Accordingly, the images of their arrest are also images of how they might appear to their followers as heroes, martyrs even. I know that Mohammed Yusuf’s followers remain begrudged over his extrajudicial execution. I know that the line is occasionally drawn from present-day Niger Delta militants to Adaka Boro. And I know that there are those who believe Ologbosere justly staged a resistance to British takeover of the Benin Empire.

Response to these images is inevitably related to extremism, violence, or a botched revolution. This is the language with which they were presented in news stories, entering into public consciousness as such. To see the triangulated photographs, however—to notice that all three men are pictured similarly several decades apart—is to consider an amplitude of meaning the news cannot express.

I cannot ignore how I often consider these men pointers to a life I am yet to live. I have never lived a life at the brink of death, for a cause, self-sacrificially. It is one thing to dismiss the actions of the men, especially Yusuf’s, as despicable and inexcusable. But in addition, it is another thing to be interested in how they can be admitted in the narratives of what I consider Nigerian. Don’t I invoke their lives, arrests, and deaths when I say I am a citizen of that country?

Sources drawn on for this essay:

- Agamben, Giorgio. “The Muselman” in Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive. New York: Zone Books, 1999.

- Berger, John, “Image of Imperialism,” in John Berger, Understanding a Photograph, ed. by Geoff Dyer. New York: Aperture, 2013.

- Boro, Adaka Isaac Jasper. The Twelve-Day Revolution, ed. Tony Tebekaemi.

- Benin: Idodo Umeh, 1982.

- Burns, Allan. History of Nigeria. London: G. Allen & Unwin, Ltd., 1929.

- Kateb, George, “Morality and Self-Sacrifice, Martyrdom and Self-Denial,” in Social Research, Vol. 75, No. 2.

- Human Rights Watch. Spiraling Violence: Boko Haram Attacks and Security

- Force Abuses in Nigeria. New York: Human Rights Watch, 2012.

- Thorp, Ellen. Ladder of Bones. London: Cape, 1956.

Image credits: Images of Ologbosere, Adaka Boro, and Yusuf available in public domain. Still image of Abubakar Shekau from an undated video.