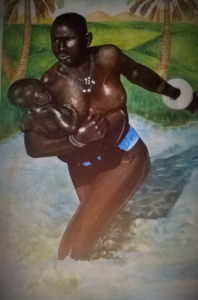

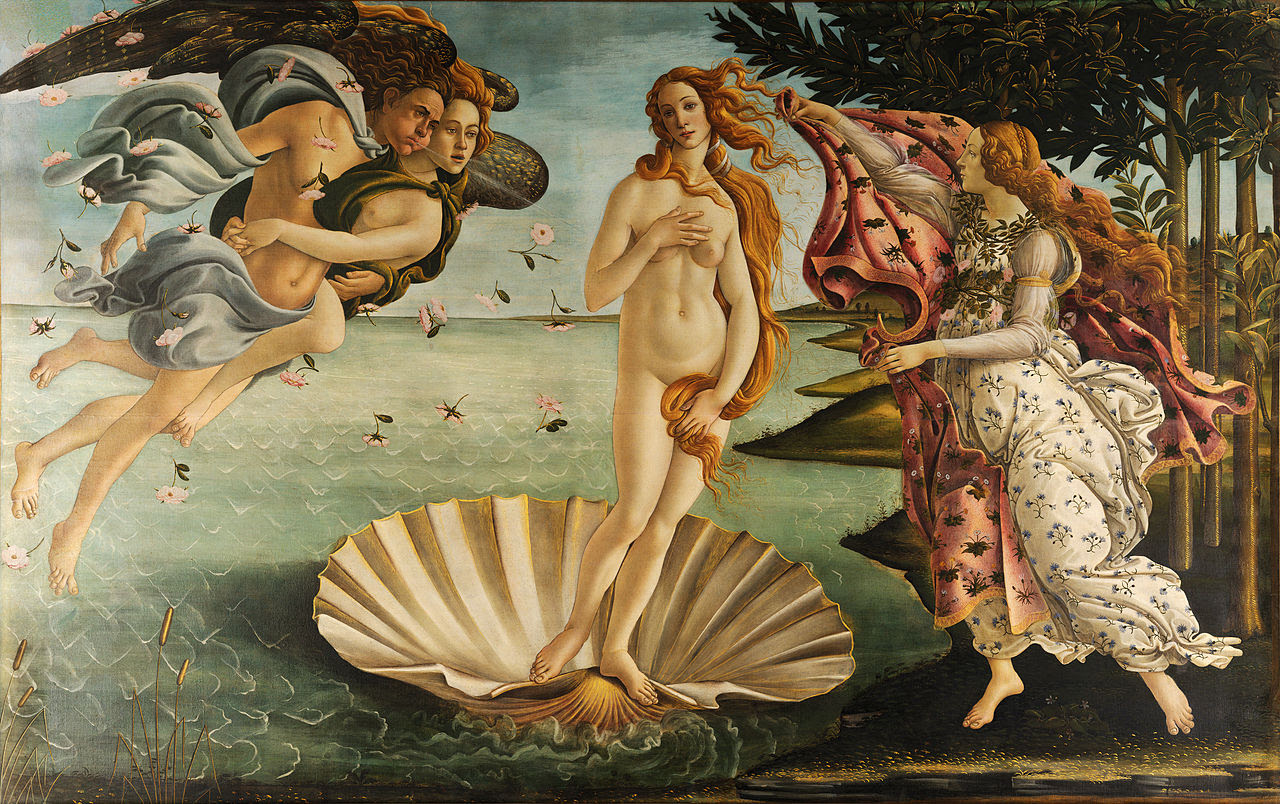

At an art exhibition in October, I saw an acrylic painting of what I could only guess was a South Sudanese woman with a baby rising out of a river. The painting by South Sudanese artist Akot Deng was part of a regional exhibition showing at the Nommo Gallery in Kampala, featured alongside several other paintings and sculptures from the East African region. The painting reminded me of speci!c tropes in Western Art History, and thus, part of my fascination with the painting had to do with seeing it as a South Sudanese version of the Italian Sandro Botticelli painting of a Venus on a clamshell, from the 15th century, called The Birth of Venus. Given that the emergence of modern painting in East Africa is mostly rooted in colonial education, I was curious about the nature of the painting as a reimagination or re-production of Western Art History. I had such questions as: what does it mean to represent the black subject as Venus; what happens when African artists appropriate from a Western canon; what is the meaning of the Venus rising out of a river in contemporary times?

This painting haunted me. I photographed it with my phone and shared it with a couple of friends, who found it rather strong. They commented on how the South Sudanese woman is depicted holding a child. As a depiction of motherhood, it was hard not to consider a relationship between the South Sudanese artist and the somewhat archaic notion of a motherland. Being that the country in question, and its capital, Juba, has been at war with Khartoum, many people have immigrated to the South, and one could see how the painting might reflect this longing for home from the perspective of a displaced person. There were others who noted the physical strength of the woman holding her child in one arm and making powerful strides as she comes out of the water, compared to the Western Venus who seems to hover on top of the water with poise. This comment echoed the essentialism that has marked the black woman within colonialism. However, my initial thoughts revolved around the photographic work of Leni Riefenstahl, the German photographer, most popularly known for her landmark work, The Last of The Nuba (1973). The painting seemed, for me, to have a natural precedent in Riefenstahl’s photography.

Although I merely suspected it, I was pleasantly surprised to !nd out that the painting was indeed a copy of a photograph from 1989. The mastery with which the artist recreated the water beads that sat on the body of the woman pointed to a careful study of the photograph. There was also the exaggeration of the subject’s breast size, and the darkening of her skin color, imposing a masculine gaze onto the subject. This photograph was taken around 1989 after two women photographers Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher undertook a major survey of what they described as African Ceremonies. Reviewing this volume of photography, the art historian Allen Roberts pointed out the link with Riefenstahl: “Primitivist photography has antecedents and most notably in the African pictures of Leni Riefenstahl, and the photos are marvelous in composition and color, but Beckwith and Fisher make a spectacle of Africa, and many will challenge their artistic project.”

I took a special interest in Roberts’s description of the book as primitivist photography, because it paid attention to not only the subject of the book, which was the fantasy of the African as a ritualized being, seen as nothing else if not practicing rituals, but it did what another reviewer described as the careful cropping out of modern life. In other words, this was a subjective depiction of Africa as a place of magic and ritual.

Last year, the art critic Orit Gat asked: “What about the comment section?” She was referring to the way in which Internet users contribute to art discourse via the comment sections of online blogs and articles. This is an interesting digression for me because I wonder if by writing this essay I am rehearsing primitivism.

I wrote a review of a photography book by an Italian photojournalist on sex workers in a red-light zone of Kampala. This review, published on Africa is A Country, received four comments, two of which have stayed with me. The !rst described me as a racist. “The frequency and length with which the author reminds us over and over again that Mr. Sibiloni is photographing ‘black women’ as to just women; and the author’s knack for citing the photographer’s own skin color, makes this piece of remarkable othering and exoticism; while it is in-depth and sheer in the veneer of academic, this bridges the gap between, and breaches, constructive thought into the pretty-much rudimentary racist.” With this response, I reflected on the meaning of exoticism in relation to “black women.” Could it be that by merely writing the word “black woman” several times in the review I had created a sort of literary pornography? Was I, by offering an analysis of the work of Michele Sibiloni, participating in the very genre of primitivism?

The answer to some of these questions lies in the second comment. “Yeah, I was thinking the second comment. “Yeah, I was thinking the same thing, what self hate? An African writing about Africans and identifying them as: “black” what ignorance?” Something was happening here. The debate in the comment section had gone beyond the photography itself, or even the “black women” depicted therein. The Internet users on Africa is A Country, wanted to refer to me not only by my writing—which they found “academic”—but they went ahead to pro!le me as “black” or as “African.” This process seemed familiar. It was the reclaiming of the primitivism genre as a domain for Whites Only. In other words, I was being told, categorically, that my race had no right to comment on an Italian’s photographs of black women. However, beyond their racial profiling of me, as an author, this idea—”An African writing about Africans and identifying them as “black”—demonstrated a lack of knowledge on my part, that naming Africans as “black” was reserved for Whites Only. This was a reeducation for me on contemporary visual culture’s linkage to colonial-era segregation, and racism, via a (mostly) liberal website.

Readers of Africa is a Country had picked up on the racial discourse in my article. I may have been unaware of the danger of my own exploration of primitivism in the article. The title itself, Pornography and Photography, sought to argue only one side of the argument, which showed ways in which black female sexuality has been recorded on camera since the 19th century. In short, I did not write the much longer article that would show a history of photographing female sex workers on the African continent since the 19th century. I might have shown how exactly racial discourses shaped African colonies in the early 20th century, and how racism—which is called “tribalism” in the modern African context—persists in modern African life.

On exoticism and the black female body, art historian Deborah Willis describes the “relation between white man and native woman (as) similar to that between colonizer and colonized country, where exotic transgression was seen as a return to primitivism, to an immediacy of passion that Western custom had long since rejected.”1 The racial discourse was already tied to colonization, especially in the propaganda that led up to the occupation of colonies in Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean. Africa was long exoticized by European colonizers as a “fertile” Negro woman long before Negritude poets depicted “her” as such. The fertility of the black woman symbolized, in colonial propaganda, the richness of the land in the Caribbean and in Africa.

The contradiction here, particularly in the field of photography, returns when allegories for colonial wealth in Africa and the Caribbean are conflated with depictions of black women. In this sense, the notion of the Black Venus is detached neither from colonial propaganda nor Western Art History. Photography, often deceptive, creates an exoticism for colonial purposes. In many ways, this colonial legacy is implicit in depictions of the black body in Western Art History. The poet Robin Coste Lewis describes this as white subjectivity; that is, the black person is not the subject, but rather it is the colonial appropriation of the black body.

The black body was also the scientific object of much late 19th and early 20th century anthropology. We read about Riefenstahl’s project in South Sudan, and that German photographer’s obsession with the physical body. Susan Sontag, who reviewed The Last of the Nuba describes Riefenstahl’s career as embodying the Nazi idealism of both perfect beauty and the perfect body. “For Riefenstahl is the only major artist who was completely identified with the Nazi era and whose work, not only during the Third Reich but thirty years after its fall, has consistently illustrated many themes of fascist aesthetics.” Sontag readily admits that the Fascist aesthetic has to do with primitivism. But not only that, it has to do with—in relation to the Nuba of South Sudan—”turning people in things.” The subject of Riefenstahl’s work remains the primitive impulse, the glorification of an apocalypse, and these ideas are both easily projected onto the Nuba, in ways that transform personalized experience into grandiose death ritual, that transform aesthetic beauty according to the Nuba into an art of submissiveness to the mighty force of destruction (here, it is the “extinction” of a race).

The comment section of Africa is a Country might, after all, be the place to question if the Nuba have any notion of aesthetics. I’ve been asked often if my home country, been asked often if my home country, Uganda, has any art. Subsequently, the shocking realization is that I could even practice art criticism. The artistic traditions of African people have been translated into primitivist discourses, and in the realm of Riefenstahl’s photography, into fascism. Dinka Woman with Baby is therefore a primitivist, if not fascist, title.

In the realm of art history, can we speak of the African subject? We learn from cultural theory that “what we call ‘the self’ is constituted out of and by difference, and remains contradictory, and that cultural forms are, similarly, in that way, never whole, never fully closed or ‘sutured.'”2 In this sense, our cultural history in East Africa may be occupied by the discourses of primitivism and, if not, fascism. However, that is not the full account of this cultural history.

Dinka Woman with Baby is part of a larger and growing cultural and political history of South Sudan, which the painter Akot Deng is aware of. The modern Sudanese painter may seek to recreate Botticelli’s Venus rising out of a river, but this is done in contemporary times, in which a civil war in South Sudan times, in which a civil war in South Sudan has forced thousands to migrate into Uganda and Kenya. The black Venus holding a child, in this sense, also represents not only the Dinka ritualistic submission to the greater forces of extinction, but it also represents the notion of Sudan as a motherland, upholding its citizens, even in the midst of civil war.

There is considerable evidence that South Sudan and its people have impacted East African politics. Here, I’m speaking about colonial politics and military nationalism. During the period of Britain’s occupation Dinka, Nuba, and other then Sudanese people, were recruited to suppress insurgency in the region, such as the Kenya emergency of 1952. Many of the soldiers that fought on behalf of Britain in World War I and II were of Sudanese origin. The military regime that led Uganda in the 1970s—consolidating the Uganda Ri”es, the colonial armed forces—comprised predominantly of the Sudanese.

Speaking about this regime’s attitude towards women, Ali A. Mazrui wrote that: “Idi Amin appointed Princess Bagaya as “Idi Amin appointed Princess Bagaya as Uganda’s !rst woman Foreign Minister. She was really a symbol of empowerment, although she struggled to remain a symbol of liberation.” We now know that the extent of this symbolic act reached demeaning proportions after Bagaya rejected the military dictator’s sexual advances. She was, then, slut-shamed publicly in the national newspaper. Mazrui shows, in the same paper, that the shaming of women in power is typical of colonialism, and particularly the shaming of black women: “In Africa after European penetration, black women have sometimes suffered both as women, and as Blacks. As far back as 1706, a young woman, holding her baby son, was burned at the stake on the border between present-day Angola and Zaire. She was Dona Beatrice, otherwise known as Kimpa Vita.”

The racism of colonial governance, as told by Ali A. Mazrui, has exposed itself in its disgust for the nude black body. While anthropologists were drawn to the physical height as well as linguistic “superiority” of Dinka, Madi, Maasai, and other Nilotic people, there is the disgust for what is described in a 1905 anthropological survey of the East Africa Protectorate by Charles Eliot:

“The want of decency, in the narrower sense of what we consider adequate clothing, is very remarkable. Natives on the coast, who have any pretensions to be Mohammedans, of course, observe strict propriety in this respect, and some un-known in!uence introduced similar ideas into Uganda, which is the more remarkable as most of the neighbouring tribes are conspicuously nude. But with these two exceptions, the native races of East Africa show an entire absence of the feelings which elad (sic) the European and Asiatic to cover their bodies. The motive may have a touch of the sentiment of the Greek athlete, and pride in a well developed form, but most natives appear to be simply in the state of Adam and Eve before the Fall, which is also that of the animals, and to have no idea of indecency.”

Comparisons to Adam and Eve before the Fall indicate primitivism in this analysis. It takes me back to the notion of the black Venus rising out of the water. The black subject cannot assume a place in civilization except if she were fully clothed and practicing Western Christian morality. However, the black Venus painting by Akot Deng breaks those barriers, by reclaiming the Dinka woman from primitivism, and thrusting her into modern Sudanese art. The meaning of Venus rising out of a river is no longer only viewed simply from the perspective of indecency or even from fascist aesthetics, but she is another Kimpa Vita rising out of the ashes of colonial and postcolonial violence.

1. Deborah Willis, “La Vénus Noire,” in The Black Female

Body: A Photographic History. Temple University Press, 2002.

2. Stuart Hall, “Introduction,” in Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. SAGE Publications, 1997.

Image Credits:

Akot Deng, East African Connect. Nommo Gallery. 2016. Image courtesy of the author.

“Dinka Woman with Baby” courtesy Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher.

Image of the painting by Botticelli in public domain.