Something can be said about encounters with strangers in public bathrooms, specifically women bathrooms. There is the horror and discomfort of being with a stranger in a space requiring privacy, but also, there is often that brief intimacy that—from time to time—is shared by these strangers. Perhaps intimacy is the wrong word for it. Maybe kindness, extended from a stranger to another when she needs it most. Many a times I have cried in public bathrooms, only to find comfort on the shoulders of a stranger. Or times when I’ve run out of tampons and in no shape to go to the nearest store, I’ve had to rely on the kindness of a stranger. As I think of this, I

nearest store, I’ve had to rely on the kindness of a stranger. As I think of this, I am reminded of a question often asked during inane dinner conversations: why do women go to bathrooms together? This is said to be one of the “many things” about women that “baffles” men, whatever that means.

When I was in primary school, the girls’ bathroom was some kind of “safe” space. Here, we hid behind the walls and spoke about our collective fear, hate (sometimes love) of the school administration, of boys, and other girls. It is where we hid from the rest of the world. I think about this often, about the kind of space the bathroom continues to provide me, now no longer a young girl.

Beyond the kindness of strangers, I have found myself paying specific attention to graffiti in bathrooms. And just as travelers collect mementos from places they have been to, I have been collecting images of texts on bathroom walls and thinking

with them about this space and what it means as a platform of expression for women.

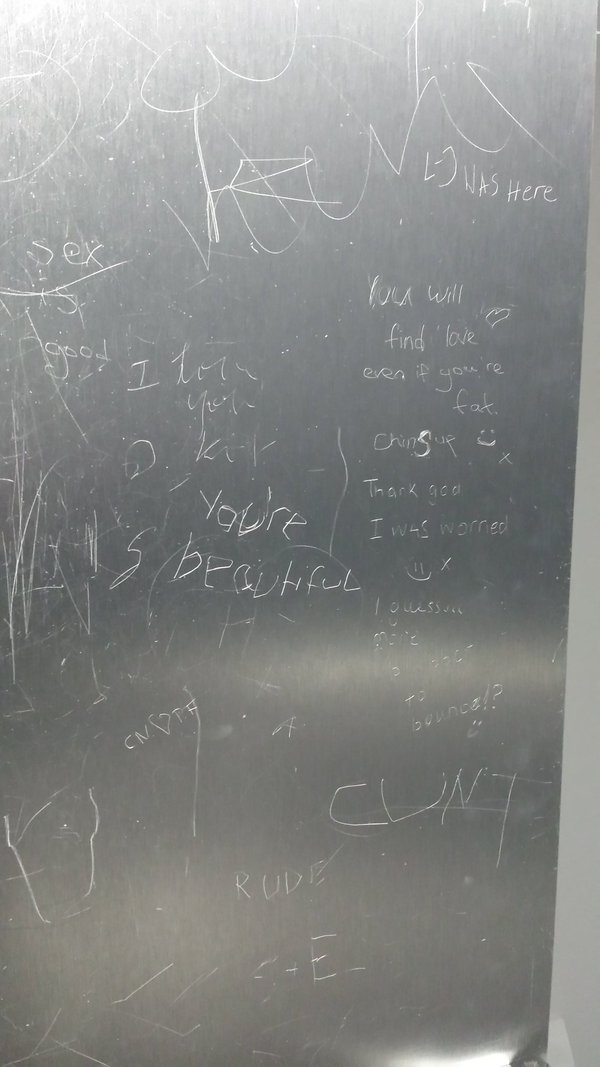

Save for the few times I have been in gender-neutral bathrooms, most of what I have collected is from women-only bathrooms. Of these images, I am particularly fond of this one, taken in a restaurant in Nairobi.

Unlike a lot of bathroom graffiti often sprayed on the wall or written by pen, the words in this image are carved on the wall, with a key or a sharp pocket knife, I imagine. I think about the patience of writing the messages in this picture, this deliberate investment of time and energy

One of the texts reads:

I was here

As with a lot of graffiti, it is a presence that wants to proclaim itself, a presence that does not want to be forgotten, even though it lacks a body and a name.

And then other texts:

Sex is good

Cunt

There is something these fragments, these texts, say about a city, its language, its desires, and the things it refuses those who inhabit it. The above text for example forces me to think of the kind of language the privacy of this space allows. It is a language undaunted by judgement, by the pressures of an audience, by shame.

Here you are, alone, free to say whatever you wish to say and go.

And so, I think of women and the policing of the language used by women.

Swearing—the patriarchal world has repeatedly told us—is not the “language of a lady.” This same world also tends to dismiss women-talk, calling it gossip or whining. Literary spaces have for years been dismissive of women and their whining. Literary spaces have for years been dismissive of women and their stories, and there exists a whole history of women adopting male or gender-ambiguous pseudonyms for these same reasons. I am also reminded of anonymous Tumblr pages and the freedom this anonymity has provided women, specifically black women.

And so in the bathroom space, women are free to tell stories of heartbreaks, of shared anger, of the violence of the world to women without judgement or shame. We speak of love, our suppressed desires for other women, for men, we speak our fears and our insecurities.

Keguro Macharia who, in thinking of these spaces and theorizing how queer lives exist in Kenya, writes:

How might a cum stain on a bathroom wall theorize? How might

it reach for freedom? More precisely, how might reading a cum

stain on a boarding school bathroom wall reach for freedom?

What might such fragments tell us about how and where queer

desire lives and thrives and imagines and dreams?

In this same image, another person writes:

You will find love babe, even if you are fat.

In most women bathrooms, this seems to be the repeated message. There is that affirmation that one is beautiful, that one is, to borrow Ann Daramola’s words on Twitter, “surrounded by love.” There is swearing, but there is also love-sharing, despite the world.

And to the one who promises love, another one writes a response:

Thank you, I was worried.

It is a conversation between strangers. A dialogue. There is some pleasure in that. I imagine that for those who write these fragments, feedback is rarely expected and rarely, if ever, received. One writes and leaves. And for the reader too, as with reading a book, this is a private act, completely devoid of an audience. Confronted by the fragments on the wall, one decides on how to interact with them, an

interaction that is coloured by our own experiences of the world, or just an impulse in the moment.

Sometimes, there is laughter, other times a recognition of the struggles or insecurities these texts bear. We recognize ourselves in them, they entertain, but they also anger us, they violate the idea of a safe space. Racial slurs, homophobic comments, and all manner of insults are common. In the image above for example, I find myself pausing at the person who writes “cunt” and those who—in other walls I have photographed—leave homophobic comments and racist slurs. In the course of this article, I have repeatedly called this a “space safe,” but I am aware of the complications of this term, this false promise that there is safety in the shared, whether it is shared ideologies, pains, insecurities, etcetera. While the space I speak of here represents community for some and might bring kindness from a stranger, for others, it is a place of profound violence.

Writing about safe spaces in campuses, Roxane Gay says:

There are some extreme, ill-advised and simply absurd

manifestations of the idea of safe space. And there are and should

be limits to the boundaries of safe space. Safe space is not a place

where dissent is discouraged, where dissent is seen as harmful.

And yet. I understand where safe space extremism comes from.

When you are marginalized and always unsafe, your skin thins,

leaving your blood and bone exposed. You live at the breaking

point. In such circumstances, of course you might be inclined to

fiercely protect yourself, at any cost. Of course you might become intolerant. Of course you might perceive dissent as danger.

In many feminist platforms, I have heard friends deny or hesitate around the idea of safe spaces, preferring rather to call such spaces intentional spaces, because safety is never guaranteed. And so lately, even as I make these claims here, I am teaching myself to stop and interrogate humour, comfort, and safety in public places. Questions constantly haunt my thinking. Who is laughing? Who is comfortable? At whose expense? Who is safe?