In 2010, the designer Ebi Atowodi published Nigerians Behind the Lens, a book containing the work of nine Nigerian photographers. The photographers—Adolphus Opara, Amaize Ojiekere, Andrew Esiebo, Emeka Okereke, George Osodi, Jide Alakija, TY Bello, Uche Okpa-Iroha, Yetunde Ayeni-Babaeko—are united by contemporaneity. Their contemporary, so to speak, was the first decade of Nigeria’s twenty-first century, the years between 2000 and 2009, when the photographs were taken. Time unfurls in this specific manner, in a large format book, a visual warehouse of contemporary Nigerian experience.

For months my skepticism has intensified about what can be referred to, with a sweeping gesture of the hand, as “Nigerian.” The adjective, in describing the noun, falls within its shadow, and hardly escapes it. It is simple enough to live in Nigeria, and typify that particular experience Nigerian. It’s simple enough, as well, to qualify people who live in it Nigerian. In speculating about what’s essentially Nigerian, I am not comforted by the notion of a multi-ethnic nation, united in diversity. Instead, terrified constantly by the daredevil insistence on “one Nigeria,” in the face of seismic agitations for secession. I attend to Atowodi’s book with the sum of these disconsolations.

In relation to Nigerians Behind the Lens, I want to assume, however pedantically, that there is something fundamentally Nigerian about photographs taken in Nigeria. I could expand on my claim by making a list of books produced to showcase Nigerian photographs—including for instance Peter Obe’s Nigeria: Decade of Crises in Pictures, Kunle Tejuoso’s Lagos: A City at Work, and more recently exhibition catalogues for Dey Your Lane! Lagos Variations and the Lagos Open Range Festival. What, however, is characterized in photographs taken in Nigeria? How do I respond in a manner that does not reduce to an essential what should be probed for ambiguity?

The distinction is admittedly contrived. Photographs owe their credibility to a moment in a given place. That is, if there is place called Nigeria, any photograph taken in a Nigerian city will be classified as a Nigerian photograph. Most photographs are valued for their social significance—cherished for events recorded, faces ennobled, or memories conjured. As social items, exchanged within particular frames of reference, photographs localize what they depict. Recall the example of replacing statuettes with photographs in parts of Yorubaland. Upon the death of a twin, a statuette was made to represent the deceased, and appeasement offerings made to it. Increasingly, in the 1970s, deceased, and appeasement offerings made to it. Increasingly, in the 1970s, photographs replaced the statuettes. The living twin was photographed, and the negative doubly exposed on the same print. Hence, the sense in which the history of a place acts upon the images produced within it is the sense in which one might articulate what’s peculiar about the photography of that place.

The book, Atawodi states in her introduction, contains “a varied selection of images which are snippets from richer bodies of work.” It is possible, by extension, to place the images in conversation, one image brushing up against the other, evocative. In some cases, the evocation is of a historical kind.

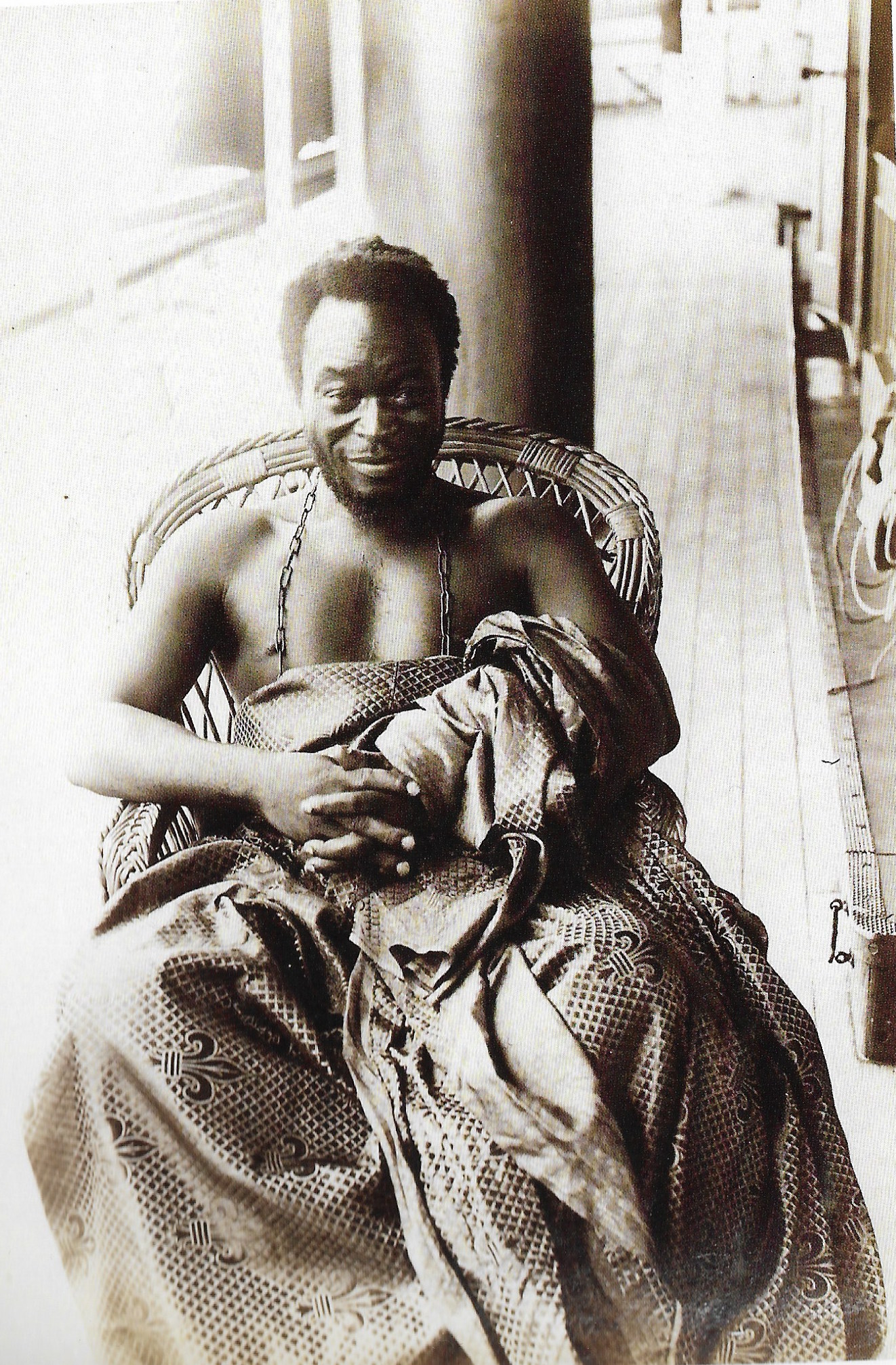

In 2009, when Adolphus Opara took portraits of deities from the regions of Osun and Osogbo, the resulting photographs portray men and women with admirable gravitas. While traveling extensively in southwestern Nigeria, Opara was compelled by the need to document and preserve a religion, subject otherwise to fetishization and derision. The photographs he returned with, in classic Victorian style, were of subjects adorned in brilliant clothes, displaying the accouterment of their exalted offices, seated or standing. Their images recall another series of their exalted offices, seated or standing. Their images recall another series of photographs taken during the colonial era—images of imprisoned royalty, taken in the Victorian era as well.

In particular, there’s Jonathan Adagogo Green’s portrait of King Ovonramwen of Benin, who in 1897 was captured by marauding British forces, deposed, and exiled. The photograph fails if it is expected to convey a subdued man. His head is bent slightly forward. Isn’t that a smirk on his face? His shoulders and arms are bare. His eyelids are puffed: perhaps he’s sleep-deprived. But that smirk intensifies the tension in the photograph. I notice a chain circling his neck, extending downwards, likely binding his unseen feet. He is covered from his chest to his legs with a robe imprinted with royal insignia. Green’s portrait presages Opara’s. For, as royalty cannot be stripped in a simple gesture of binding an Oba’s feet, the spiritual relevance of Yoruba deities remains intact in spite of radical changes in religious practices. Emissaries of an Iconic Religion predates Nigerian Monarchs—George Osodi’s portraits of Nigerian kings—by only a year. Like the deities, the kings are decked in grandeur, sometimes surrounded by courtiers, unmistakably assertive.

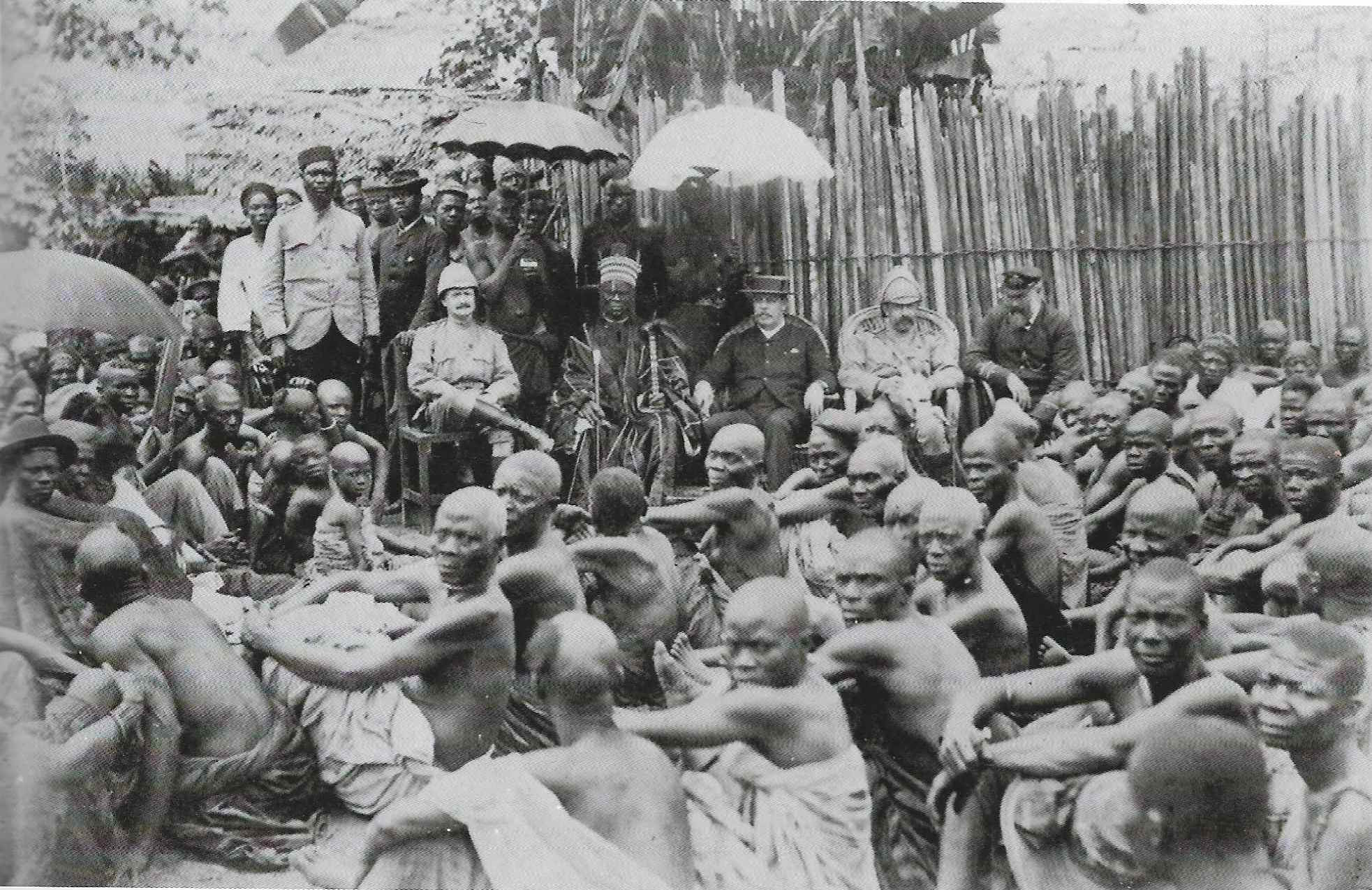

Yet the kings and deities, and other Nigerians in exalted positions, gain authority from the lower class, those covered in grit and sweat. Those at the top exist because there are those at the bottom. The earliest photograph I know, amply describing this paradox, is one taken in 1891 by N. Walwin Holm. The event depicted is a durbar, the annexation of Ado to the Lagos colony. Holm’s framing foregrounds a crowd of men sitting on the floor, mostly with hands on their knees, looking sidelong at the camera. In the background of the image, the Chief of Ado is seated beside Sir George C. Denton, governor of Lagos. There are three other members of Denton’s military staff. The photograph carries with it a residuum of dissent, although it depicts the peaceful takeover of the region. The half-naked men on the floor, who represent the ruled, are unsmiling. Their expressions, in fact, are of discomfort and wariness.

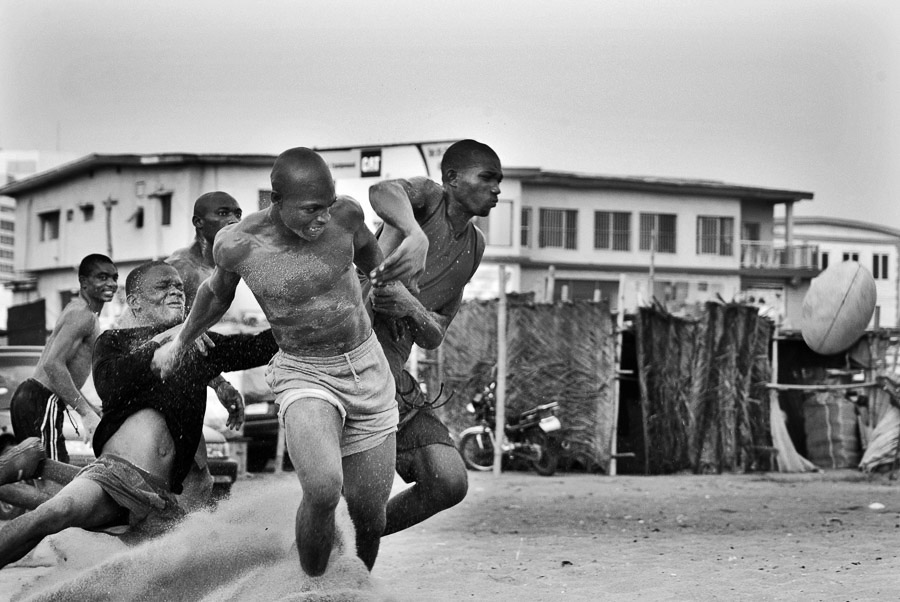

The first photograph in Atawodi’s book is Adolphus Opara’s “Rugball 6.” It’s the upclose portrayal of a sweaty man. This face belongs to a man playing rugball with other men. In “Rugball 10” five men are chasing a spherical ball. They stretch for the ball, pulling at each other. Most of their feet are buried in sand. As if to highlight the resonance of Opara’s Rugball series, especially the photograph of men chasing a ball, a photograph by Andrew Esiebo shows a man in midair. He’s jumping over a tyre, a footballer in training. Esiebo’s series, Surviving Dreams, includes several photographs of a football coach, his life in and out the pitch, his alternate vocation as a pastor inspiring young men in his neighbourhood. This coach watches over the jumping man.

Perhaps no country can lay claim to a peculiar narrative of survival. In Nigeria, regardless, the narrative particularizes as squandered opportunities to put abundant resources to use for the welfare of all. Esiebo’s Surviving Dreams and Opara’s Rugball, as any project documenting Nigeria’s youth, characterizes activity, almost in a frenetic manner: The man who ties the lace of his Lacoste sneakers. The bouncer who grabs a crossbar, his muscles taut. The silhouette of men in a football field with their hands aloft. Images of this sort in the book are, men in a football field with their hands aloft. Images of this sort in the book are, undeniably, composed of male emanations. The photographers I have discussed so far are men. It is as though men are drawn to men, male privilege to male privilege, one man’s insufficiency to another’s. Social spaces are gendered in a patriarchy. “This project made me conscious of gendered spaces. I’m not used to being in women’s spaces.” I asked Andrew Esiebo about his photographs of barbershops, and that was his response.

There’s a sweaty woman in the book, in a photograph by George Osodi. It’s night, the woman is smiling, wearing a raffia hat, and at work. Her name is Tapioca Uzere. The light that illumines her face, and indeed the entire photograph, is light from flared gas. Compared to Opara’s sweaty subject, who is unsmiling and in motion, Tapioca’s smile acknowledges the photographer in a way that also acknowledges the viewer. There is nothing in her condition—a woman who makes a living in one of the most polluted parts of the earth—that presupposes a smile. But this is a foreknowing smile. She knows she will be looked at as a woman at work, and that foreknowing smile. She knows she will be looked at as a woman at work, and that in spite of her polluted town. Despite her struggles her glance ennobles.

If woman is a metaphor, it is the axle on which grace turns—considering certain photographs by Yetunde Ayeni-Babaeko in the book. The initial images, from the 2009 series Drei Dreiecke are monochromatic portrayals of a nude model. There is nothing much of interest to me in the series, as all I can recall is encountering models on a runway, dexterously placing one foot before the next. But Drei Dreiecke unravels into another series, Water Bodies, where the women are positioned less fashionably. The subjects, underwater, are photographic impressions of a mythologized mami-wata. In “Legs,” the legs of a female model is poised in water, laps and knees and calves and feet, causing a slight ripple.

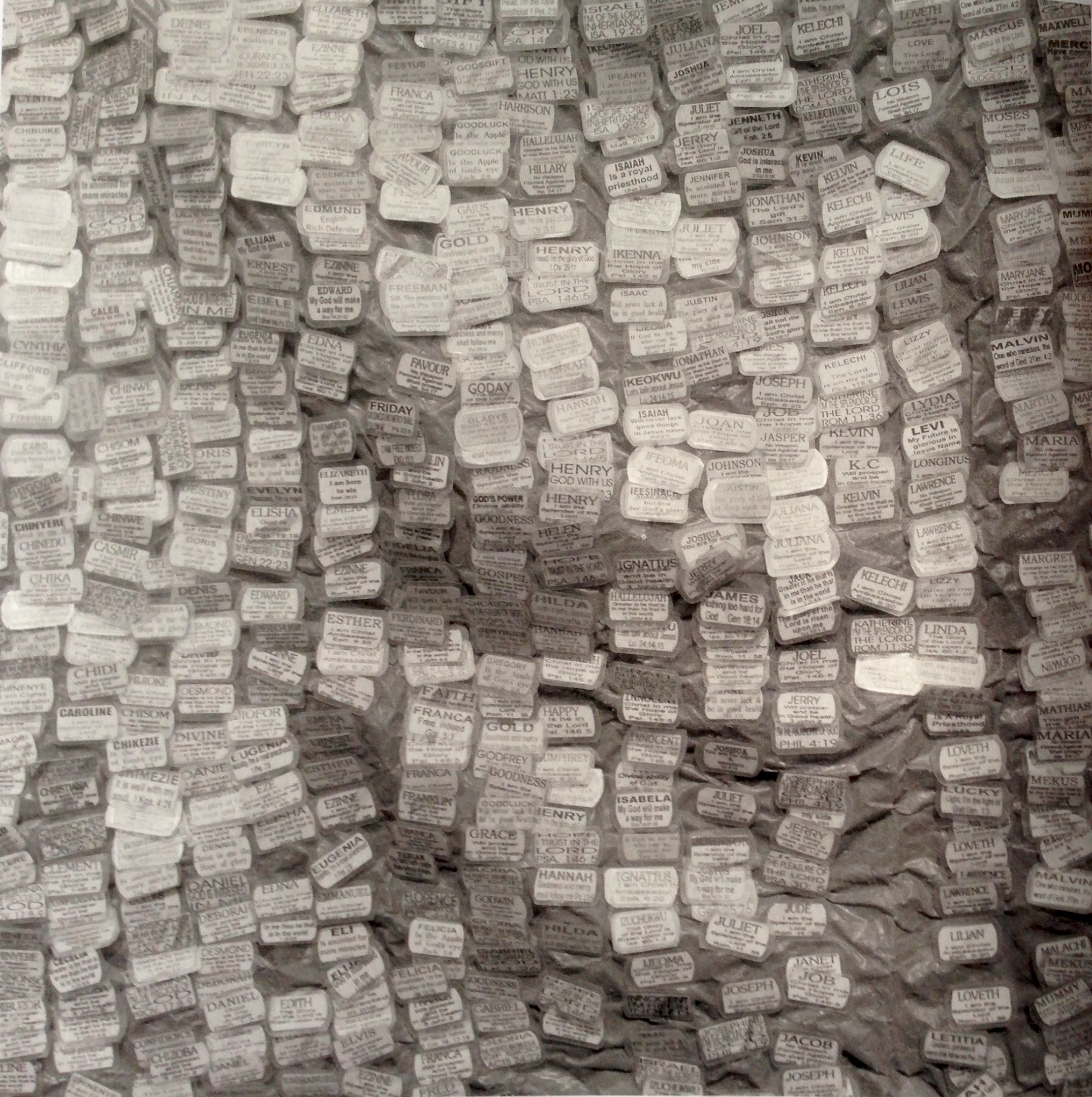

A ripple of water, an undulation, is also combination of like things. Clusters, a series of photographs by Amaize Ojeikere, depict the wave-like clustering of items for sale. “Name-Tags” is a picture of names and their meanings. Spread on tarpaulin, each tag is a few inches wide. “Nigerian Home Videos” is picture of a stack of home videos, extending beyond the frame. An untitled photograph is of secondhand shoes, laid out for sale. These photographs, together or severally, are a quintessential expression of lives reliant on commodity. People wear shoes, see movies, pin names on their chest, and they do this a lot. From the photographs there is no way to miss the scale in which these commodities are exchanged. The nametags reveal a range of aspirations, peddled for sale—“EDITH: The glory of God is risen upon me,” “MUMMY: Christ in me the hope of glory,” CHIKEZIE is the apple of God’s eye,” GLORIA the perfect knowledge of God, LEVI: my future is glorious in Jesus name…”

Most aspirational Nigerians, poor and dispossessed, yet not disillusioned, place their hope on an unseen God. The intensity of their faith, in a sense, reveals the limitations of their lives. A photograph by Emeka Okereke illustrates this fact. “Portrait of a Trader, 2,” I’ll argue, extends from Ojeikere’s Clusters. A woman sits encircled by polythene bags. These bags are filled with charcoal, tied up. Indeed there are sacks of charcoal behind her, around her. The bags are gathered for sale. She’s pictured in a pose, in a glance away from the camera, holding a blackened rag. It is this rag, and the pause of her hands, that points me to the fact she’s dealt with charcoal for a good amount of time, and to the certainty that she will trade charcoal for longer.

The image on the opposite page is another “Portrait of a Trader,” this time of a man staring at the camera. He sits with his right leg raised, a hand on the raised leg. The other leg is stretched until it rests on the edge of a pavement. Both feet are bare, but there’s a slipper atop the pavement. Beside him is a pile of fabric bound for sale. I assume immediately he’s a hawker, and this is a portrait of him resting awhile. My assumption, although a low rung on the ladder of knowledge, directs me to his right hand. The hand lightly grabs his ankle. To grab an ankle, the hinge of the feet, is to nurse it after constant movement—a gesture familiar to all who walk for hours.

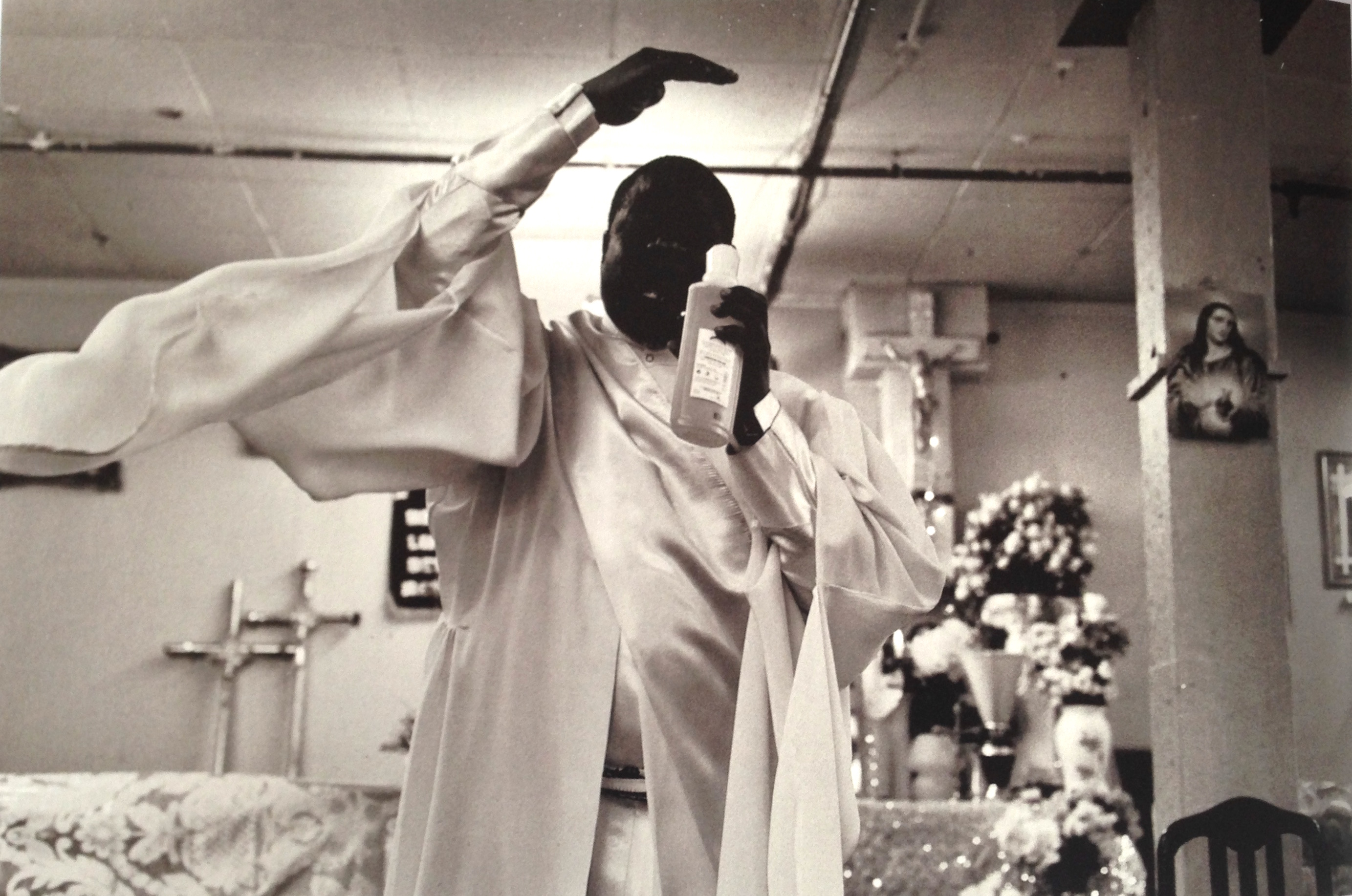

Hands are tenuous instruments. Nowhere in the book do they become more prominent as in photographs from the series Friends of the Veranda Man by T.Y. Bello. In a church hall, a priest’s hand, held aloft, becomes a kind of arc above his head. By a certain stretch of the imagination, a priest in that pose is equally an illustration of shelter, of the arc to which believers go to take refuge. Not a mere allusion. Consider the crucifixes, hung on the wall or placed against it. The priest, although his face is darkened and barely recognizable, has epitomized his gospel—“Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” The hands are perhaps the only part of the body that can unambiguously suggest a beckon.

The simple fact of a hand, in another photograph by Bello: a man holds a cigarette between his thumb and index finger of his right hand, and places the other hand below his hairline, shielding his forehead. Are these the hands of an anxious man? If he shields his forehead, does he expect to be protected from a sense of foreboding?

“Every feeling waits upon its gesture,” wrote Eudora Welty. “Perhaps,” wrote the novelist Ivan Vladislavić, taking the idea further, “every gesture will beget its twin, every action find an echo, every insight become a catechism, like some chain reaction that can never be halted. The concatenated universe.”

The concluding part of this essay will be published in the next issue of The Trans- African