In the short story The Man by E.B Dongala, “the man” breaks into the president’s palace and kills him. It is not clear how he manages to pass through the impregnable security system “contrived by an Israeli Professor with degrees in war science and counter-terrorism.” These chambers, Dongala writes, are protected from the people by perimeter walls, armed soldiers, a water-filled moat of immense depth filled with crocodiles and Caymans, a ditch full of black mambas, barbed wire, broken glass, huge mirrors reflecting everything, scrutinising the visitors’ gestures. The list goes on. Still, the man finds his way into the palace where the “holy of holies” sleeps and kills him.

While the president in Dongala’s story has made himself unreachable, inaccessible to the people he believes himself to be beloved, he remains everywhere. The “father-founder of the nation, the enlightened guide and saviour of the people, the great helmsman, the president-for-life, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and the beloved father of the people” is everywhere and nowhere.

Dongala further writes:

It was a statutory requirement that his portrait should hang in

all homes. The news bulletin on radio always began and ended

with one of his stirring thoughts. The television news began,

continued and finished in front of his picture and the solitary

local newspaper published in every issue at least four pages of

letters in which citizens proclaimed their undying affection.

I read this story for the first time in 2002. At the time, Kenya’s opposition leader, Mwai Kibaki through a coalition of opposition parties, had inspired hope in the masses that something else other than KANU, the ruling party since independence, was possible.

There is something chillingly familiar about the president in E.B Dongala’s The Man. The above passage in particular specifically resonates with the earliest memories I have of Kenya’s second president Daniel Arap Moi. I remember my grandmother holding her head close to the small National Panasonic radio at the top of each hour, eagerly listening to the first five minutes of the news bulletin.

We need to hear what Mtukufu Rais has to say. She would shush us. We need to know what Mtukufu Rais did today. “Mtukufu.” “Highness.” “His Excellency.” After the newscaster played a few clips from the president’s speech of the day, the radio would be switched off to save on battery power, until the next top-of-the-hour

news. I do not recall her having any interest in the presidency beyond this routine, this need to obediently listen and consume information fed to her repeatedly through KBC, the state-owned radio station. Listening mutely seemed like a civic duty. There were no interjections, no comments on what the radio said. What the

radio said satisfied.

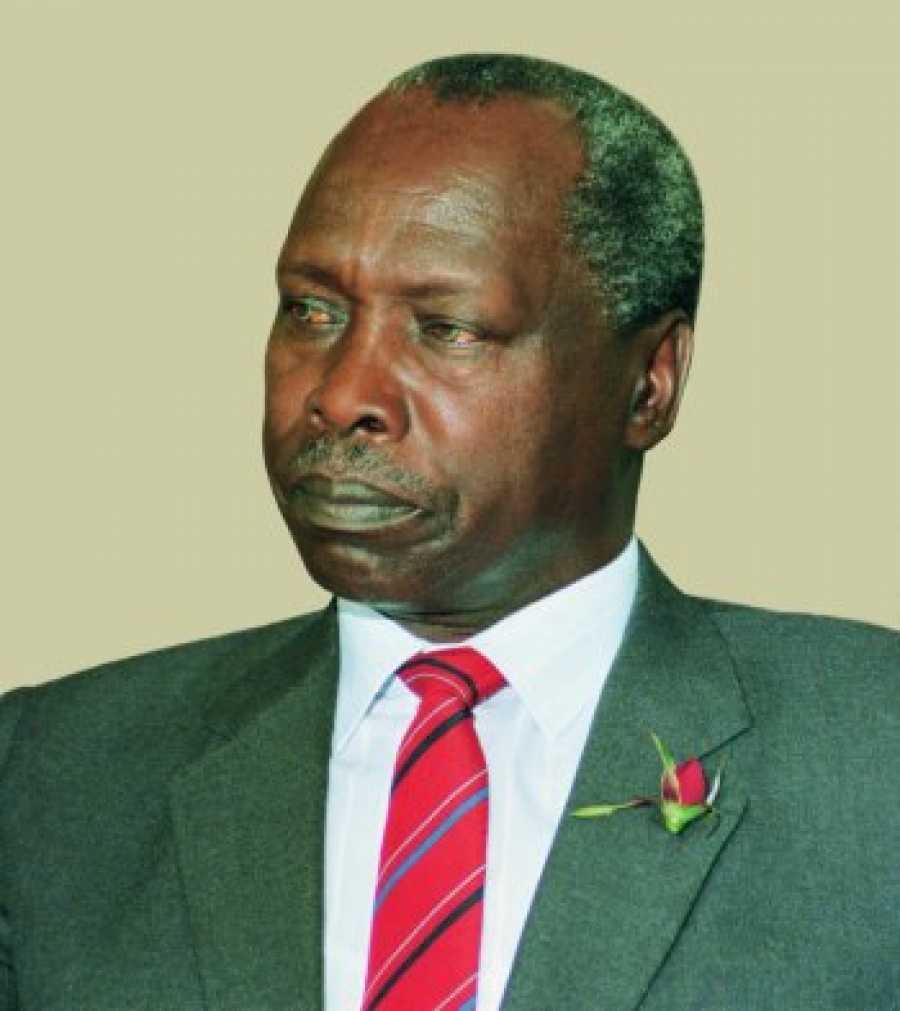

Most specifically, I have memories of the president’s face staring down at me from the high walls of the local shop throughout my childhood. He was in the headmaster’s office, in the staffroom, somewhere above the barber’s mirror, in the shack where we bought paraffin, in people’s houses.

His was not a kindly face. It was a face that inspired fear, the cold face of a man who commanded respect from the one who was looking. In the official presidential portrait, Moi punctuated the dreariness on his face with a red shirt and a matching

boutonnière on the left lapel of his dark-grey suit. Constantly, we were reminded of the importance of this face. We were asked to respect it. In the loyalty pledge, we recited our respect for it. We were reminded how the ruling party, KANU, was one of the factors that promoted “the feeling of national unity, of belonging to one

single sovereign nation.”

Somewhere along the way, Daniel Arap Moi, and everything about him, including his portrait, his rungu, his party KANU, even his hand gestures became the unwritten symbols of “national unity.” Baba na Mama wa Taifa, Father and Mother of the nation, the foundation upon which the nation is built, the thread that held

Kenya together. The president’s portrait assumed symbolic usefulness in all public (and some private) spaces, and even though it was not enshrined in the law that one must hang it, it became a matter of routine and many were convinced that it was indeed a requirement. Proclaiming one’s patriotism was important. It was the

safer way to live.

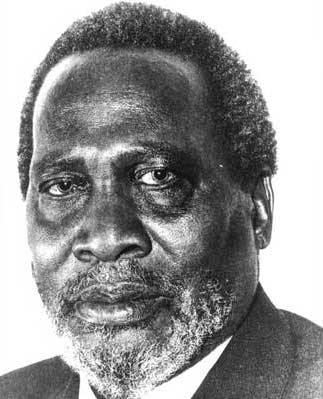

This not-so-subtle self-glorification is something that Daniel Arap Moi inherits from his predecessor, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, “the Founding Father of the Nation,” in whose footsteps he follows through the Nyayoism philosophy. The portrait of Jomo Kenyatta displayed in public spaces during his time and even after his death

was firm and chilling. Like his name “Mzee,” his portrait exuded that feel of elderliness that commanded unparalleled respect and reminded the citizens that someone wiser than they are was in charge. And who dared question the wisdom of the old? Who?

The portraits of these two first presidents echoed each other in what they demanded of the citizen. The portrait of the president proclaimed itself and instilled fear. With its incisive stare, it intimidated. Fear and intimidation sometimes begot allegiance. This face called to those who were looking at it, those who were in its presence to respect power. Like the mirrors in the E. B Dongala’s

palace, it scrutinised every gesture of the one who watched it. It is not the viewer who was looking at it, but the portrait that was looking back. It entered into private homes and sought to be worshipped. Constantly, it reminded the citizens that without it, without these men, a country was impossible.

Like his predecessors, Uhuru Kenyatta, the current president, has also invested highly in his portrait. In the 2015 annual report on “measures taken and progress achieved in the realisation of national values and principles of governance,” it is stated that:

…to demonstrate patriotism, the Ministry of Information, Communication and Technology in conjunction with Brand

Kenya Board […] produced and circulated 200,000 copies of the

official portrait of the President of the Republic of Kenya to

Government institutions and to the public.

The official portraits of the most recent presidents, Mwai Kibaki and Uhuru Kenyatta take a different trajectory. While they command respect, these two are presented as leaders who are somewhat accessible, perhaps even pleasant and sociable. Uhuru Kenyatta’s portrait especially is harmonious to his general style of photographing, which presents him as one of the “cool kids”. He is the president who takes selfies and wears skinny jeans. Still, like their two predecessors, Uhuru’s portrait and that of Mwai Kibaki position themselves as significant symbols of the state.

While the law does not expressly say that the president’s portrait must be displayed in public spaces, this issue remains contentious even today. Earlier this year, Kakamega traders were given a directive by Kenya’s Interior Ministry to display the portrait of President Uhuru Kenyatta or get fined. Siaya governor, Cornel Rassanga, had also called other governors from the opposition party Cord to remove Uhuru Kenyatta’s portrait from their offices and replace it with Raila Odinga’s, the opposition party leader. Immediately after independence, Kenyan businessmen of Asian origin became the subject of discussion in parliament for

failing to display the president’s portrait, as was the tradition with the Queen’s portrait when Kenya was still a British colony. To refuse to display this face then is to deny the existence of such a power. It is to refuse one’s allegiance to this power.

In the history of propagandist portraiture, the need to be revered is not only specific to Kenyan presidents or African presidents. Kenya seems to follow in the steps of its colonialists, who required the portrait of the Queen to be displayed in all public spaces in colonial Kenya. In 1500s Roman art, emperors were sculpted and displayed in public for propaganda value and to exalt Roman power.

There is truth in the place of the presidency as a national symbol. However, I have wondered about this face and how it contributes to the collective identification of Kenyan-ness. It is a face that demands to be remembered, the face of one who does not want to be forgotten. It is as if [he] fears that one day, the citizens will wake up and they will not recognize [him], that the books will not document [him]. And so the face makes itself omnipresent.

I recall once, coming across a little booklet with songs of praise for Daniel Arap Moi, with his portrait as the front cover and the same portrait as the back cover. One was not enough. One is never enough.